National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

The official seal of NACA, depicting the Wright Flyer and the Wright brothers' first flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina | |

Logo | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | March 3, 1915 |

| Dissolved | October 1, 1958 |

| Superseding agency | |

| Jurisdiction | Federal government of the United States |

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) was a United States federal agency that was founded on March 3, 1915, to undertake, promote, and institutionalize aeronautical research.[1] On October 1, 1958, the agency was dissolved and its assets and personnel were transferred to the newly created National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). NACA is an initialism, i.e., pronounced as individual letters, rather than as a whole word[2] (as was NASA during the early years after being established).[3]

Among other advancements, NACA research and development produced the NACA duct, a type of air intake used in modern automotive applications, the NACA cowling, and several series of NACA airfoils,[4] which are still used in aircraft manufacturing.

During World War II, NACA was described as "The Force Behind Our Air Supremacy" due to its key role in producing working superchargers for high altitude bombers, and for producing the laminar wing profiles for the North American P-51 Mustang.[5] NACA also helped in developing the area rule that is used on all modern supersonic aircraft, and conducted the key compressibility research that enabled the Bell X-1 to break the sound barrier.

Origins

[edit]

NACA was established on March 13, 1915, by the federal government through enabling legislation as an emergency measure during World War I to promote industry, academic, and government coordination on war-related projects. It was modeled on similar national agencies found in Europe: the French L'Etablissement Central de l'Aérostation Militaire in Meudon (now Office National d'Etudes et de Recherches Aerospatiales), the German Aerodynamic Laboratory of the University of Göttingen, and the Russian Aerodynamic Institute of Koutchino (replaced in 1918 with the Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute (TsAGI), which is still in existence). The most influential agency upon which the NACA was based was the British Advisory Committee for Aeronautics.

In December 1912, President William Howard Taft had appointed a National Aerodynamical Laboratory Commission chaired by Robert S. Woodward, president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. Legislation was introduced in both houses of Congress early in January 1913 to approve the commission, but when it came to a vote, the legislation was defeated.

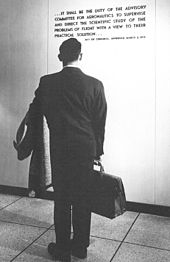

Charles D. Walcott, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution from 1907 to 1927, took up the effort, and in January 1915, Senator Benjamin R. Tillman, and Representative Ernest W. Roberts introduced identical resolutions recommending the creation of an advisory committee as outlined by Walcott. The purpose of the committee was "to supervise and direct the scientific study of the problems of flight with a view to their practical solution, and to determine the problems which should be experimentally attacked and to discuss their solution and their application to practical questions". Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt wrote that he "heartily [endorsed] the principle" on which the legislation was based. Walcott suggested the tactic of adding the resolution to the Naval Appropriations Bill.[6]

According to one source, "The enabling legislation for the NACA slipped through almost unnoticed as a rider attached to the Naval Appropriation Bill, on March 3, 1915."[7] The committee of 12 people, all unpaid, were allocated a budget of $5,000 per year.

President Woodrow Wilson signed it into law the same day, thus formally creating the Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, as it was called in the legislation, on the last day of the 63rd Congress.

The act of Congress creating NACA, approved March 3, 1915, reads, "...It shall be the duty of the advisory committee for aeronautics to supervise and direct the scientific study of the problems of flight with a view to their practical solution. ... "[8]

Research

[edit]

On January 29, 1920, President Wilson appointed pioneering flier and aviation engineer Orville Wright to NACA's board. By the early 1920s, it had adopted a new and more ambitious mission: to promote military and civilian aviation through applied research that looked beyond current needs. NACA researchers pursued this mission through the agency's impressive collection of in-house wind tunnels, engine test stands, and flight test facilities. Commercial and military clients were also permitted to use NACA facilities on a contract basis.

- Facilities

- Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory (Hampton, Virginia)

- Ames Aeronautical Laboratory (Moffett Field)

- Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory (Lewis Research Center)

- Muroc Flight Test Unit (Edwards Air Force Base)

In 1922, NACA had 100 employees. By 1938, it had 426. In addition to formal assignments, staff were encouraged to pursue unauthorized "bootleg" research, provided that it was not too exotic. The result was a long string of fundamental breakthroughs, including "thin airfoil theory" (1920s), "NACA engine cowl" (1930s), the "NACA airfoil" series (1940s), and the "area rule" for supersonic aircraft (1950s). On the other hand, NACA's 1941 refusal to increase airspeed in their wind tunnels set Lockheed back a year in their quest to solve the problem of compressibility encountered in high speed dives made by the Lockheed P-38 Lightning.[9]

The full-size 30-by-60-foot (9.1 m × 18.3 m) Langley wind tunnel operated at no more than 100 mph (87 kn; 160 km/h) and the then-recent 7-by-10-foot (2.1 m × 3.0 m) tunnels at Moffett could only reach 250 mph (220 kn; 400 km/h). These were speeds Lockheed engineers considered useless for their purposes. General Henry H. Arnold took up the matter and overruled NACA objections to higher air speeds. NACA built a handful of new high-speed wind tunnels, and Mach 0.75 (570 mph (495 kn; 917 km/h)) was reached at Moffett's 16-foot (4.9 m) wind tunnel late in 1942.[10][11]

Wind tunnels

[edit]NACA's first wind tunnel was formally dedicated at Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory on June 11, 1920.[12] It was the first of many now-famous NACA and NASA wind tunnels. Although this specific wind tunnel was not unique or advanced, it enabled NACA engineers and scientists to develop and test new and advanced concepts in aerodynamics and to improve future wind tunnel design.

- Atmospheric 5-ft wind tunnel (1920)

- Variable Density Tunnel (1922)

- Propeller Research Tunnel (1927)

- High-speed 11-in wind tunnel (1928)

- Vertical 5-ft wind tunnel (1929)

- Atmospheric 7- by 10-ft wind tunnel (1930)

- Full-scale 30- by 60-ft tunnel (1931)

Influence on World War II technology

[edit]In the years immediately preceding World War II, NACA was involved in the development of several designs that served key roles in the war effort. When engineers at a major engine manufacturer were having issues producing superchargers that would allow the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress to maintain power at high altitude, a team of engineers from NACA solved the problems and created the standards and testing methods used to produce effective superchargers in the future. This enabled the B-17 to be used as a key aircraft in the war effort. The designs and information gained from NACA research on the B-17 were used in nearly every major U.S. military powerplant of the Second World War. Nearly every aircraft used some form of forced induction that relied on information developed by NACA. Because of this, U.S.-produced aircraft had a significant power advantage above 15,000 feet, which was never fully countered by Axis forces.[citation needed]

After the war had begun, the British government sent a request to North American Aviation for a new fighter. The offered P-40 Tomahawk fighters were considered too outdated to be a feasible front line fighter by European standards, and so North American began development of a new aircraft. The British government chose a NACA-developed airfoil for the fighter, which enabled it to perform dramatically better than previous models. This aircraft became known as the P-51 Mustang.[5]

Supersonic research

[edit]

After early experiments by Opel RAK with rocket propulsion leading to the first public flight of a rocket plane, the Opel RAK.1, in 1929 and eventual military programs at Heinkel and Messerschmitt by Nazi Germany in the 1930s and 1940s, the US entered the race to supersonic planes and spaceflight in the 1940s. Although the Bell X-1 was commissioned by the Air Force and flown by Air Force test pilot Chuck Yeager, when it exceeded Mach 1 NACA was officially in charge of the testing and development of the aircraft.[13] NACA ran the experiments and data collection, and the bulk of the research used to develop the aircraft came from NACA engineer John Stack, the head of NACA's compressibility division.[5] Compressibility is a major issue as aircraft approach Mach 1, and research into solving the problem drew heavily on information collected during previous NACA wind tunnel testing to assist Lockheed with the P-38 Lightning.

The X-1 program was first envisioned in 1944 when a former NACA engineer working for Bell Aircraft approached the Army for funding of a supersonic test aircraft. Neither the Army nor Bell had any experience in this area, so the majority of research came from the NACA Compressibility Research Division, which had been operating for more than a year by the time Bell began conceptual designs. The Compressibility Research Division also had years of additional research and data to pull from, as its head engineer was previously head of the high speed wind tunnel division, which itself had nearly a decade of high speed test data by that time. Due to the importance of NACA involvement, Stack was personally awarded the Collier Trophy along with the owner of Bell Aircraft and test pilot Chuck Yeager.[14][15]

In 1951, NACA Engineer Richard Whitcomb determined the area rule that explained transonic flow over an aircraft. The first uses of this theory were on the Convair F-102 project and the F11F Tiger. The F-102 was meant to be a supersonic interceptor, but it was unable to exceed the speed of sound, despite the best effort of Convair engineers. The F-102 had actually already begun production when this was discovered, so NACA engineers were sent to quickly solve the problem at hand. The production line had to be modified to allow the modification of F-102s already in production to allow them to use the area rule. (Aircraft so altered were known as "area ruled" aircraft.) The design changes allowed the aircraft to exceed Mach 1, but only by a small margin, as the rest of the Convair design was not optimized for this. As the F-11F was the first design to incorporate this during initial design, it was able to break the sound barrier without having to use afterburner.[16]

Because the area rule was initially classified, it took several years for Whitcomb to be recognized for his accomplishment. In 1955 he was awarded the Collier Trophy for his work on both the Tiger and the F-102.[17]

The most important design resulting from the area rule was the B-58 Hustler, which was already in development at the time. It was redesigned to take the area rule into effect, allowing greatly improved performance.[18] This was the first US supersonic bomber, and was capable of Mach 2 at a time when Soviet fighters had only just attained that speed months earlier.[19] The area rule concept is now used in designing all transonic and supersonic aircraft.

NACA experience provided a model for World War II research, the postwar government laboratories, and NACA's successor, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

NACA also participated in development of the first aircraft to fly to the "edge of space", North American's X-15. NACA airfoils are still used on modern aircraft.

Chairmen

[edit]| No. | Portrait | Name | Term | President serving under | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

Brig. Gen. George P. Scriven (United States Army) |

1915–1916 | Woodrow Wilson | |

| 2 |

|

William F. Durand (Stanford University) |

1916–1918 | ||

| 3 |

|

John R. Freeman (Consultant) |

1918–1919 | ||

| 4 |

|

Charles Doolittle Walcott (Smithsonian Institution) |

1920–1927 | ||

| Warren G. Harding | |||||

| Calvin Coolidge | |||||

| 5 |

|

Joseph Sweetman Ames (Johns Hopkins University) |

1927–1939 | ||

| Herbert Hoover | |||||

| Franklin D. Roosevelt | |||||

| 6 |

|

Vannevar Bush (Carnegie Institution) |

1940–1941 | ||

| 7 |

|

Capt. Jerome C. Hunsaker (Navy, MIT) |

1941–1956 | ||

| Harry S. Truman | |||||

| Dwight D. Eisenhower | |||||

| 8 |

|

Lt. Gen. James H. Doolittle (Shell Oil Company) |

1957–1958 | ||

Transformation into NASA

[edit]Special Committee on Space Technology

[edit]

On November 21, 1957, Hugh Dryden, NACA's director, established the Special Committee on Space Technology.[20] The committee, also called the Stever Committee after its chairman, Guyford Stever, was a special steering committee that was formed with the mandate to coordinate various branches of the federal government, private companies as well as universities within the United States with NACA's objectives and also harness their expertise in order to develop a space program.[21]

Wernher von Braun, technical director at the US Army's Ballistic Missile Agency would have a Jupiter C rocket ready to launch a satellite in 1956, only to have it delayed,[22] and the Soviets would launch Sputnik 1 in October 1957.

On January 14, 1958, Dryden published "A National Research Program for Space Technology", which stated:[20]

It is of great urgency and importance to our country both from consideration of our prestige as a nation as well as military necessity that this challenge (Sputnik) be met by an energetic program of research and development for the conquest of space. ...

It is accordingly proposed that the scientific research be the responsibility of a national civilian agency working in close cooperation with the applied research and development groups required for weapon systems development by the military. The pattern to be followed is that already developed by the NACA and the military services. ...

The NACA is capable, by rapid extension and expansion of its effort, of providing leadership in space technology.

On March 5, 1958, James Killian, who chaired the President's Science Advisory Committee, wrote a memorandum to the President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Titled, "Organization for Civil Space Programs", it encouraged the President to sanction the creation of NASA. He wrote that a civil space program should be based on a "strengthened and redesignated" NACA, indicating that NACA was a "going Federal research agency" with 7,500 employees and $300 million worth of facilities, which could expand its research program "with a minimum of delay".[20]

Members

[edit]As of their meeting on May 26, 1958, committee members, starting clockwise from the left of the above picture:[21]

| Committee member | Title |

|---|---|

| Edward R. Sharp | Director of the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory |

| Colonel Norman C Appold | Assistant to the Deputy Commander for Weapons Systems, Air Research and Development Command: US Air Force |

| Abraham Hyatt | Research and Analysis Officer Bureau of Aeronautics, Department of the Navy |

| Hendrik Wade Bode | Director of Research Physical Sciences, Bell Telephone Laboratories |

| William Randolph Lovelace II | Lovelace Foundation for Medication Education and Research |

| S. K Hoffman | general manager, Rocketdyne Division, North American Aviation |

| Milton U Clauser | Director, Aeronautical Research Laboratory, The Ramo-Wooldridge Corporation |

| H. Julian Allen | Chief, High Speed Flight Research, NACA Ames |

| Robert R. Gilruth | Assistant Director, NACA Langley |

| J. R. Dempsey | Manager. Convair-Astronautics (Division of General Dynamics) |

| Carl B. Palmer | Secretary to Committee, NACA Headquarters |

| H. Guyford Stever | Chairman, Associate Dean of Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| Hugh L. Dryden | (ex officio), director, NACA, Namesake of future Dryden Research Center |

| Dale R. Corson | Department of Physics, Cornell University |

| Abe Silverstein | Associate Director, NACA Lewis |

| Wernher von Braun | Director, Development Operations Division, Army Ballistic Missile Agency |

References

[edit]- ^ "NACA Overview". history.nasa.gov. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Murray, Charles, and Catherine Bly Cox. Apollo. South Mountain Books, 2004, p. xiii.

- ^ Jeff Quitney (May 17, 2013). "Creation of NASA: Message to Employees of NACA from T. Keith Glennan 1958 NASA". Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ Abbot, Ira H. "Summary of airfoil data NACA report 824" (PDF). engineering.purdue.edu/. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c "NASA - WWII & NACA: US Aviation Research Helped Speed Victory". www.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on December 18, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ Roland, Alex. "Model Research - Volume 1". Archived from the original on November 13, 2004.

- ^ Bilstein, Roger E. "Orders of Magnitude, Chapter 1". Archived from the original on January 14, 2007.

- ^ Dawson, Virginia P. "Engines and Innovation". Archived from the original on October 31, 2004.

- ^ Bodie, Warren M. The Lockheed P-38 Lightning: The Definitive Story of Lockheed's P-38 Fighter. Hayesville, North Carolina: Widewing Publications, 2001, 1991, pp. 174–5. ISBN 0-9629359-5-6.

- ^ Bodie, Warren M. The Lockheed P-38 Lightning. pp. 75–6.

- ^ "ch3-5". www.hq.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on September 14, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ Joskow, Melissa; Dennis, Warren (June 10, 2015). "The NACA's First Wind Tunnel". NASA History. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ John Uri (June 12, 2023). "95 Years Ago: First Human Rocket-Powered Aircraft Flight". NASA. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ From Engineering Science to Big Science: The NACA and NASA Collier Trophy Research Project Winners, 1998, P.89

- ^ "Dryden Flight Research Center historical data". NASA. Archived from the original on October 13, 2006. Retrieved December 10, 2006.

- ^ From Engineering Science to Big Science: The NACA and NASA Collier Trophy Research Project Winners, 1998, p. 146.

- ^ From Engineering Science to Big Science: The NACA and NASA Collier Trophy p. 147

- ^ From Engineering Science to Big Science: The NACA and NASA Collier Trophy Research Project Winners, 1998, P.147

- ^ Haynes, Leland R. "B-58 Hustler Records & 15,000 miles non-stop in the SR-71". www.wvi.com. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c Erickson, Mark (2005). Into the Unknown Together - The DOD, NASA, and Early Spaceflight (PDF). Air University Press. ISBN 1-58566-140-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 20, 2009.

- ^ a b "ch8". history.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on December 25, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ Schefter, James (1999). The race : the uncensored story of how America beat Russia to the moon. New York: Doubleday. p. 18. ISBN 9780385492539. OCLC 681285276. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Michael H. Gorn, Expanding the Envelope: Flight Research at NACA and NASA.

- James Hansen. Engineer in Charge: A History of the Langley Aeronautical Laboratory, 1917–1958.

- John Henry, et al. Orders of Magnitude: A History of the NACA and NASA, 1915–1990 Archived April 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- Alex Roland. Model Research: The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, 1915–1958.

External links

[edit]- U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission: The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA)

- The NASA Technical Reports Server provides access to a collection of 14,469 NACA documents dating from 1917.

- Historical digitized NACA reports from the TRAIL project are also hosted at TRAIL

- Aerospaceweb.org: Information on NACA airfoil series

- Nasa.gov: "From Engineering Science to Big Science"—The NACA and NASA Collier Trophy Research Project Winners, edited by Pamela E. Mack.